|

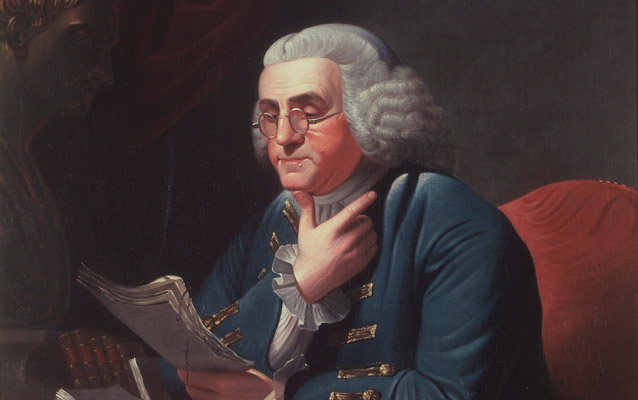

| The author, Gish Jen, 2010. [CC BY SA 3.0] via Wikimedia. |

World and Town by Gish Jen

World and Town by Gish JenMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

This book caught my eye at the bookstore but I bought Ha Jin's Waiting instead. Soon after I regretted not buying World and Town and I was compelled to go back to the bookstore and buy it. I am glad I did.

I usually find it difficult to give five stars to modern literature because I often find the classics so much better. Will this be a classic? I don't think so, but it might just be one of those long-lost gems in years to come.

This novel covers so much ground yet brings it together so well. It is a book of contrasts. Old age, youth. Children, death. Multiculturalism but from so many angles. Chinese history. Cambodian history. Vietnam veterans, the disintegration of the family farm, the end of long-term marriages, foster homes. Religion - Christianity, Buddhism, Confucianism, burial, suicide, ethnic gangs, multilingualism, academia, science versus religion, religion versus science, pets, old love, new love. Kids who say "like" in the middle of every sentence, small town life, emails from home to the diaspora (like letters that form part of the dialogue in earlier novels), music, farming, hippies.

In many ways it presents a version of the United States as it is rather than as it is imagined by some (I can only guess, but it resonates with the realities of Australia's cultural diversity). And it all concentrates on a small town in the north. I wondered if Hattie, the protagonist, would start to bore me. She just seemed so old. I think of Scott Fitzgerald who said nobody wants to read about poor people.

But Hattie is so complex, so interesting. She is nosy, an artist, a scientist, a teacher, lonely. Yet she has a drive and a sense of self-discovery that makes you forget she is an old retired Chinese-American widow living in a small town. The connections with the rest of the world, the different ideas of filial responsibility, of God's work versus the manipulation of churches that prey (not pray!) on the vulnerable.

The book even mentions the idea of "third culture kids" (something I have only ever read about in academia). It taught me a few things about adaptability and change, too (p. 232):

Even pigeons try to connect what they do with what happens to them. Really, they have no control. But they're wired to try anyway. They have a connection bias, just like people - a tendency to look for cause and effect, whether it's there or not.Did you know that "Houdini had a tool pocket in the lining of his mouth"? I didn't. Now I have to find out if it's true. Do you know (p. 246):

...what it meant to have had our structures adapted and readapted, but never fundamentally redesigned[?]I didn't. I don't know whether to call this a lovely story or an inspiring yet realistic tale. But I did love the book and I look forward to reading some more of Gish Jen's work. In an era of xenophobic nonsense, this novel sheds some light on what the world is like beneath the veneer of how things used to be.

View all my reviews

Donate

Donate

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View