|

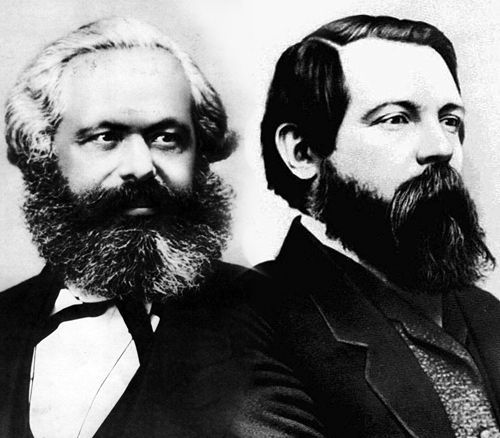

| Guillaume Guillon-Lethière's "The Death of Cato of Utica" (1795). Source: Wikimedia. |

Teach Yourself Stoicism and the Art of Happiness by Donald J. Robertson

Teach Yourself Stoicism and the Art of Happiness by Donald J. RobertsonMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

This book was recommended by Ryan Holiday at the Daily Stoic. At first, I was dismayed that it read just like a first-year textbook, with little activities in boxes throughout each chapter. But this is hardly fair. As my reading of the book progressed, and the activities became a little more complex (or at least, reflective, and some of these I will no doubt take up), I was learning. In terms of an overview of Stoicism and Stoic literature, this book provides an easy introduction, though it does tend to over-rely on Pierre Hadot. Yet there are many references and ideas that are useful, and in this the book is sound. The author also mentions an ebook that includes an additional chapter on "death", and this annoyed me no end - I hate ebooks - it should have been in the hard copy! And in the present work, the textbook tone cheapens what could have been a more substantial work. That said, I will be returning to this book time and again to mine some of the gems hidden amongst the rough.

View all my reviews

Donate

Donate

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View