|

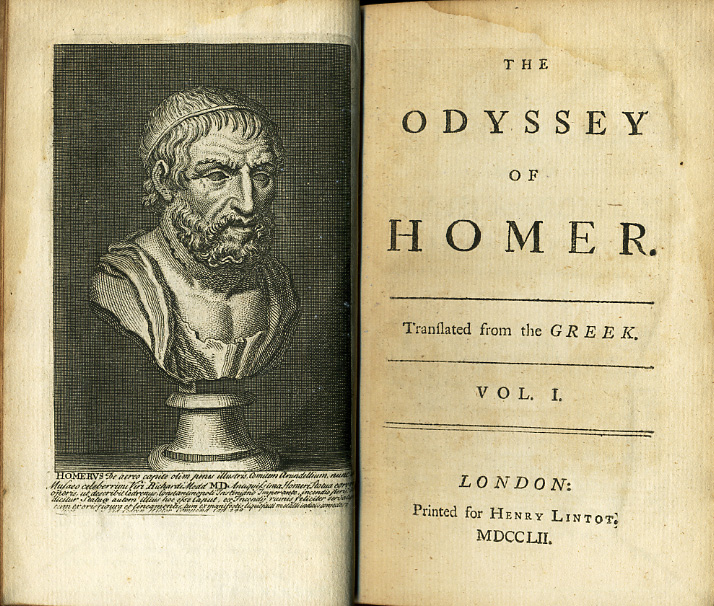

| John Stuart Mill (c. 1870). |

Utilitarianism by John Stuart Mill

Utilitarianism by John Stuart MillMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

The trouble with Mill is that you if read a few of his then-contemporary critics, and then you think you have his measure with all your modern day access to knowledge, but all along he was throwing "mind grenades" set on "delay" and they sit in your head while you go on thinking you are rather smart. So Mill mentions the Stoics and how virtue is only a means to happiness and that there are other things, too. He mentions the Sophists and how Socrates (allegedly) challenged their ancient equivalent of what is happening in higher education today. But in mentioning the development of utilitarianism from Epicurus to Bentham (and unfortunately I have not read Bentham cover-to-cover as I will do in the future), so just when I think to myself: "Mill, you really are 'drawing a long bow here' [a favourite saying of one of my favourite professors]", the mind grenade goes off and my hubris is dashed and I am glad I didn't say it out loud but there you have it - it was certainly there. There is no mention of Aristotle and the "golden mean" and how achieving a mean across the spectrum of virtues achieves happiness, but, as Mill says, there are many things that amount to happiness in addition to leading a virtuous life, so bringing up Aristotle doesn't make a good deal of sense. One interesting aspect of the essay is the long note in the last few pages where Mill extends a good deal of courtesy to Herbert Spencer, someone I have read more about in Jack London's Martin Eden than I ever did in all the other secondary sources I have read put together. While Mill does not quite agree with Spencer, Spencer claims (according to Mill) that he was never against the doctrine of utilitarianism. So the Greatest Happiness Principle it is but if we do not also take into account Mill's ideas of liberty (in On Liberty), then the present-day situation where we are told what to like and what will make us happy and many of us go along with that and eat our smashed avocado, living in our high density housing, and paying for cups of coffee that we could make at home for a fraction of the price, which are not only much better, but we could also be happier because we were actually doing something for ourselves, while, as Tolstoy or even my mother would say, "in reality", we are succumbing to the biggest scam ever and then wondering why we are not happy at all. And J.S. Mill says all this in just under 122 pages of thick paper dating from 1895, which is nice, but with each cover-to-cover completion of classic works I edge ever-closer to the abyss of what I don't know and it scares me.

View all my reviews

Donate

Donate