|

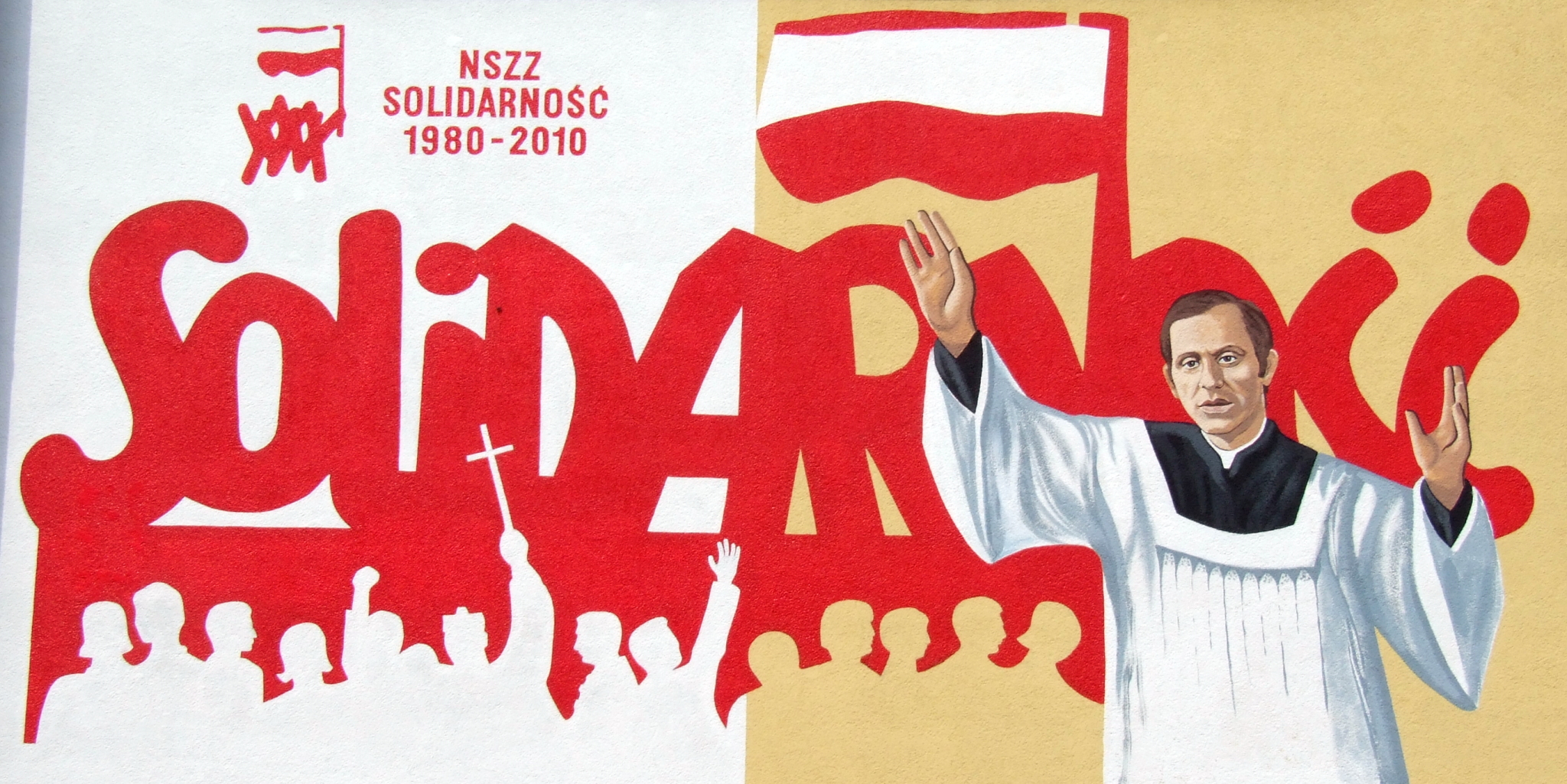

| 30-years of Solidarity mural in Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski. Photo by Krugerr (2010) CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia. |

An Advertisement for Toothpaste by Ryszard Kapuściński

An Advertisement for Toothpaste by Ryszard KapuścińskiMy rating: 4 of 5 stars

Ryszard Kapuściński was born in Belarus and grew up in Poland. He is regarded as one of the greatest journalists of the twentieth century for his coverage of revolutions and coups in places including Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. In the 1950s, he began working for the Polish Press Agency (PAP), a communist state-run news service. It is interesting that, since Kapuściński's death, he has been criticised for "making up" the news he reported in order to perpetuate his legend. Yet Kapuściński believed that poets were best-placed to be journalists, as they knew both style and brevity, and his works of fiction, including novels and short stories, were enough to put him in the running for the Nobel Prize in Literature. This book of four stories covers the lives of the poor in Poland. The stories include: An Advertisement for Toothpaste, Danka, The Taking of Elżbieta, and The Stiff. In very few words, Kapuściński's short stories bring to life the subtitle of the work these stories are drawn from: Nobody Leaves: Impressions of Poland, which were only translated into English in 2017. To borrow from various other critics, Kapuściński's style is most notably "sympathetic" to the people he writes about. The biography published by Artur Domoslawski after Kapuściński's death provides the most "plausible" critique, not so much of his work, but of his ability to tell a story while being somewhat liberal with the facts. But on reading these four stories, I have an image of life in the poorer parts of Poland. The reader can see the church in the shadow of the commune, one can feel the strange place of Poland as a country of white people who were, in effect, colonised by whiter people, and apparently Kapuściński used this to his advantage when travelling through revolutionary/post-colonial Africa to give him access (and escape) from places no other white person could. To come back to Poland, and the focus of these four short stories, I can picture it in my mind as if it had been painted for me, but written in a minimalist style that provides sufficient structure for me to draw the rest. Not like Hemingway's icebergs, for there is sufficient meat on the literary bones, but in such a short space as to indicate the extent of Kapuściński's genius. I expect to return to Kapuściński's work again soon, and I can only hope his books are nearly as good as these short stories. These, as far as I can tell, are all regarded as "travel writing" (a genre I enjoy). The recent emergence of Kapuściński's "lost" (i.e. untranslated) works in English leaves me wondering how much literary brilliance is left waiting to be discovered throughout the world. It also makes me wonder where we would be without books such as this accessible Penguin series of translated works. Kapuściński was fluent in several languages and witnessed much of the undoing of colonialism and communism. It is little wonder that his work is so good, and one can only imagine how his experience of the world shaped his craft. And rather than be envious, I must admit to feeling pleased that I can experience his travels in the safety and comfort of my own home, for surely such a life was hard work. I like to think that Kapuściński's "magical journalism" comes from the magic he sought through his living, and that some of his magic rubs off on those who are fortunate enough to read his works.

View all my reviews

Donate

Donate

.jpg)