|

| The majority of working Australians drive to and from work. AAP/Dan Himbrechts |

Getting serious on roads reform is one way our political leaders can get back on track

Michael de Percy, University of Canberra

Structural economic reform is hardly the stuff of epic election campaigns. But tax reform, including some form of road user charging, is well overdue for Australia.

Road user charging will involve a shake-up of all road-related revenues and how we pay for and use our roads and transport infrastructure. This will require federal leadership and the agreement of the states and territories. The Commonwealth’s fuel excise and the states’ and territories’ car registration fees will be affected.

Further reading: Road user charging belongs on the political agenda as the best answer for congestion management

The road to reform

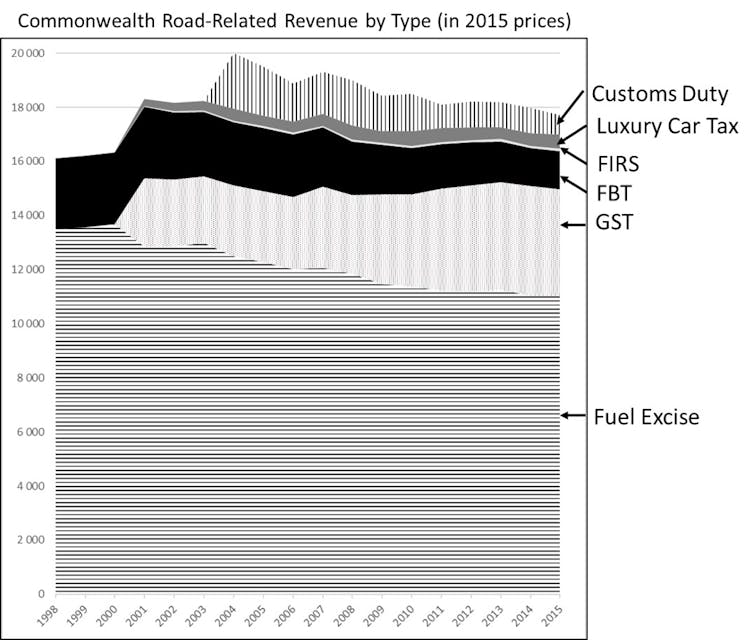

The Commonwealth’s fuel excise is obsolete. Despite the reintroduction of indexation, the fuel excise revenue base is steadily declining and will eventually disappear.

Fuel excise is obsolete because fuel-efficient and electric vehicles use less fuel. It is also unfair, because people who can afford the latest Tesla cars will pay nothing in fuel excise. And it does not signal market demand for, or go directly back into, building and maintaining transport infrastructure.

|

| The contribution of fuel excise to road-related budget revenue is shrinking. (A$‘000s in 2015 prices) BITRE |

Also, the fuel excise provides a perverse incentive by encouraging motorists with fuel-efficient cars to drive more. However, road user charging incentivises behavioural change that can help reduce traffic congestion.

The typical urban worker commutes for about one hour each work day, and time spent commuting is rising. The majority of working Australians drive to and from work. Australians are not getting any healthier, and longer commuting times are at least part of the problem.

Further reading: What’s equity got to do with health in a higher-density city?

If we do nothing, traffic congestion in capital cities is expected to cost A$53.3 billion by 2031 – or 290% more than it did in 2011.

Some argue that “peak car” will save the day. But per-capita car ownership figures mean nothing if the number of actual cars isn’t reduced. Driverless cars may even make things worse.

Why it’s been difficult to achieve

The reality is that roads are the “least reformed of all infrastructure sectors”. And roads, according to competition expert Ian Harper, are the:

… only example of an infrastructure asset, where the government owns the great bulk of the asset, funded through the tax system and given away for nothing.

So, why is road reform so hard?

Road pricing is long overdue and it’s happening elsewhere. But it’s as big as the GST, and it could prove to be just as unpalatable.

Truckies already pay for their use of the roads, and moves are afoot to increase the charges to more accurately cover the cost of the damage trucks do to the roads.

This is supported by the railways, which have effectively cross-subsidised trucks ever since the truckies stopped cross-subsidising them. But politicians are reluctant to tackle road pricing for private cars because motorists don’t like the idea.

Further reading: Trucks are destroying our roads and not picking up the repair cost

There has at least been some movement. Urban Infrastructure Minister Paul Fletcher announced in 2016 that an eminent Australian will conduct a study into the impact of road user charging for light vehicles.

What reform did for Hawke and Howard

The recent Democracy100 event at Old Parliament House was held in response to mounting dismay at the state of today’s politics. Speaking at the event, former prime ministers Bob Hawke and John Howard recommended a bipartisan approach. Focusing on key reforms to “rejuvenate the economy”, like roads reform, would do the trick.

While that may sound uninspiring, Howard observed that public esteem for politicians “has fallen in a time when there’s not been major reform”.

Howard and Hawke are two of the top three longest-serving prime ministers in Australian history. Both are living proof that major reform agendas can win elections. Howard oversaw the introduction of the “never-ever” GST; Hawke set the stage by undoing protectionism and dragging Australia into a global market economy.

And what do we have to lose? It’s clear self-centred professional politics isn’t working.

Australians expect parliament to do the hard work of reform, instead of playing dress-up and acting for the cameras. And history shows voters reward that hard work with electoral success.

Michael de Percy, Senior Lecturer in Political Science, University of Canberra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Donate

Donate