|

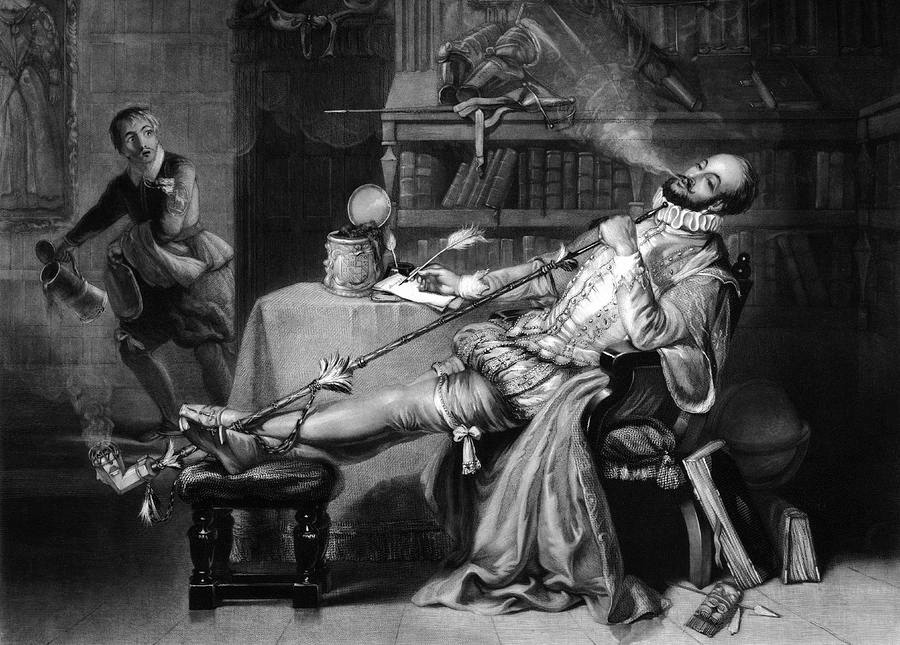

| "Raleigh's First Pipe in England" - an illustration included in Frederick William Fairholt's "Tobacco, its history and associations". [Public Domain] via Wikimedia. |

Poems by Walter Raleigh

Poems by Walter RaleighMy rating: 3 of 5 stars

I must admit I had no idea Sir Walter Ralegh (alternatively spelt Raleigh) was a poet. This volume is interesting as it outlines the purpose of such poetry as a form of "appropriate" court communication that would otherwise be unacceptable in ordinary speech.

The book includes some of the poetic responses to Ralegh's work, especially from Queen Elizabeth and Ralegh's arch-rival, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. These two engaged in literary as well as political struggles. From what I have read about Ralegh, he was a key figure in the English Renaissance, and many members of the aristocracy dabbled in poetry.

This book includes some of Ralegh's translations of classical Greek and Roman works into rhyming poetry, no doubt reflecting his education at Oxford (which was never completed). The ABAB rhyme scheme was quite common in many of the works, but several of the poems include ABBA and ABABCC rhyme schemes in the stanzas.

I was surprised that such rigid rhyme schemes were used and the book develops a sort of rhythm that only appears to be interrupted in the section where poems "attributed" to Ralegh seem to miss a few beats.

Two poems by Sir Henry Wotton, "The Character of a Happy Life" (p. 109) and "Upon the Sudden Restraint of the Earl of Somerset, then Falling from Favour" (p. 111) are worthy of quoting (respectively):

How happy is he born and taught, That serveth not another's will... This man is freed from servile bands, Of hope to rise or fear to fall, Lord of himself, though not of lands, And, having nothing, yet hath all.

And:

Virtue is the roughest way, But proves at night a bed of down.

I sense some Stoic training in these lines. Wotton was a member of the House of Commons and an English diplomat before becoming provost of Eton College.

From this small snippet of history, there is little wonder that Shakespeare emerged during this period, often regarded as the height of the English Renaissance.

It was interesting to see Ralegh's use of smoke (from tobacco) and smoking pipes in his poems. Surprising, too, that Shakespeare died two years before Ralegh, supposedly from drinking, whereas Ralegh was beheaded.

One of the many smoking stories about Ralegh suggests that he was nonchalantly smoking his pipe in the window of his cell in the Tower of London as he watched Essex being executed.

I have generally avoided this period in history as I am yet to do a cover to cover reading of Thomas Hobbes Leviathan, and I am dreading a reading of the tome of Shakespeare's complete collection that is sitting there waiting for me when I can read without distraction.

Yet all roads in English literature are leading to this period in history, and it was a pleasant surprise to learn something new about someone I had only ever known in the history books as a soldier and a maritime explorer.

Donate

Donate