|

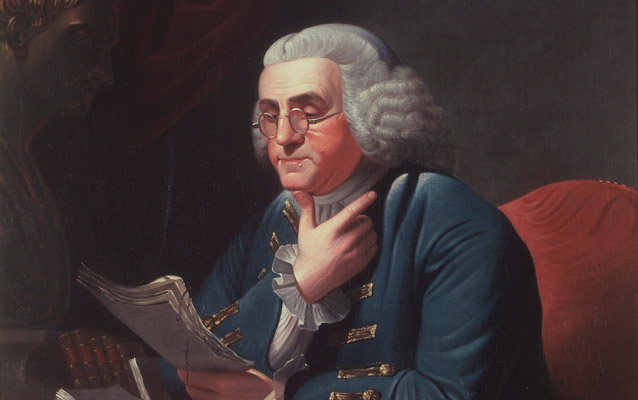

| Benjamin Franklin by David Rent Etter, after Charles Willson Peale, after David Martin (1835). National Park Service photo [Public Domain]. |

The Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Franklin by Carla Mulford

The Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Franklin by Carla MulfordMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

I have taken Mortimer Adler's advice to heart and so I try to read an author's work before delving into "companion" volumes. But there were many questions I had about Benjamin Franklin, in particular his autodidacticism and his thirteen virtues. How did this happen? What resources did he draw on in developing this process? What did he mean by "Moderation"? This volume, edited by Carla Mulford, answered many of my questions in the first two chapters: "Benjamin Franklin's Library" and "The Art of Virtue". Funnily enough, the first thing I noticed is that Franklin had a habit that was mirrored by Adler (p. 15):

Marginalia provide a way to make a book more practical as well as more personal.

Franklin also found the need to organise his books, although his personalised system was much more pragmatic than mine (p. 18). I discovered, too, ideas about Franklin's pedagogy. For instance (p. 53):

The lecture, the sermon, and all forms of face-to-face hierarchical instruction seemed to Franklin to avoid enlisting people in the creation of mutual understanding and of new forms of knowledge. Such one-sided articulations forced people to accept established truisms, unexamined claims that served and preserved the old order.

Further (p. 54):

His memoirs document his abandonment of methods of forceful assertion and concerted argument in favour of an equivocal, Socratic method.

Franklin saw "enlightened reason" as what we would call today a "democratic" faculty (p. 78), and he believed that (p. 79):

...all received knowledge could and must be tested empirically.

Franklin's views on religion are interesting, if not pragmatic. He advocated for Congress to begin with opening prayers (p. 100) (this still happens in the Australian Parliament) and saw religion as a way of keeping "the ignorant masses from sloth and insurrection" (p. 83). In terms of virtues, Franklin looked not only at individual virtues, but those in relation to "social customs through an evaluation of their results" (p. 108). One point that clarified the dilemma I had noticed but could not articulate (p. 142):

Franklin... simultaneously preached the doctrines of self-denial and good living.

There is so much more in this small volume but best of all it is an academic work. Which means my marginalia focuses almost exclusively on the detailed notes and references provided to each of the essays. I wouldn't recommend reading this before at least reading Franklin's autobiography, but as a companion to the Great Man, this volume is excellent.

Donate

Donate