|

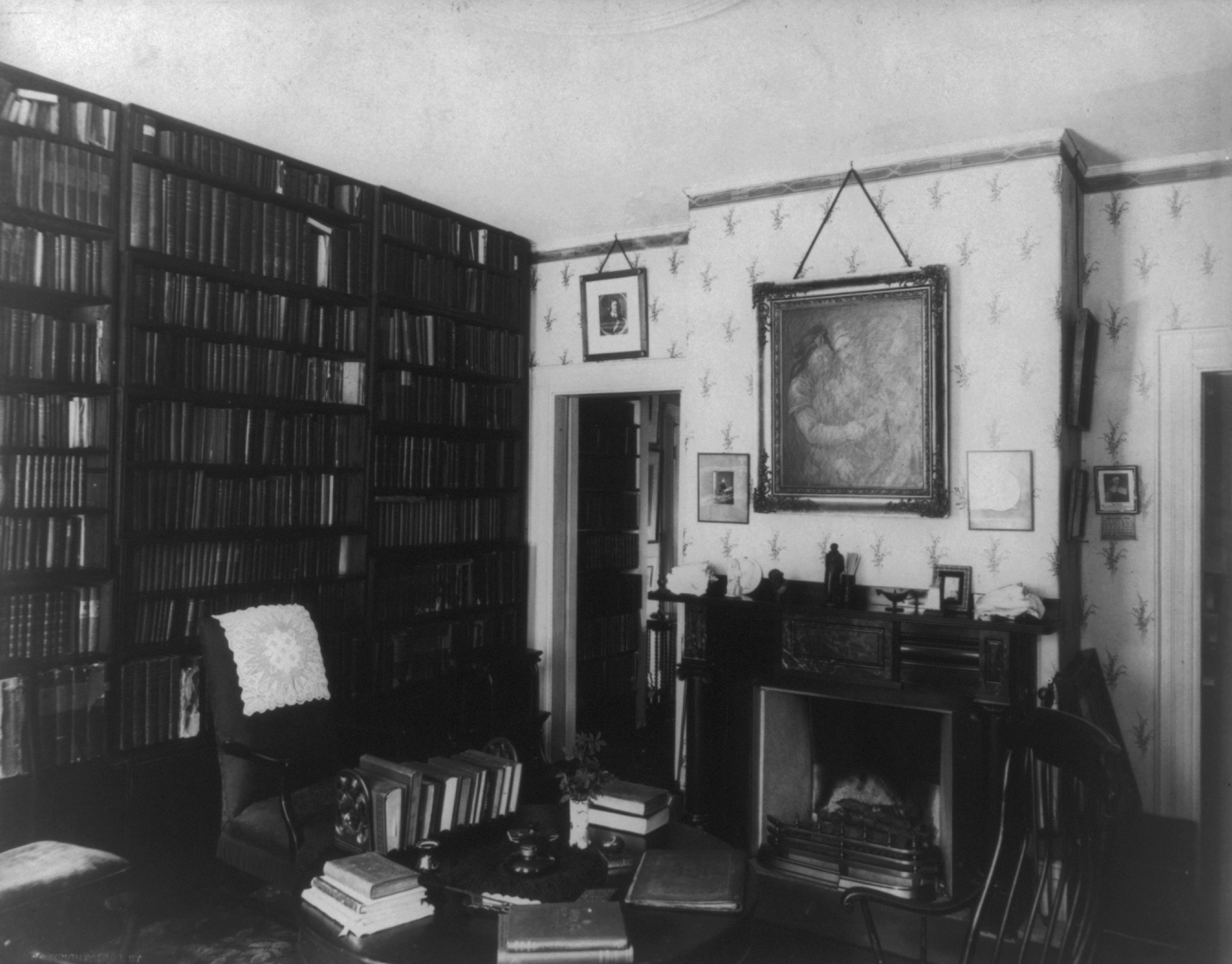

| Faith and Reason united, by Ludwig Seitz, circa 1887. Public Domain via Wikimedia |

The Discourses by Epictetus

The Discourses by EpictetusMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Today's entry in Ryan Holiday's The Daily Stoic reads: "There is hardly an idea in Stoic philosophy that wouldn't be immediately agreeable to a child". This is how I feel about Epictetus' The Discourses. It all seems like so much common sense once argued in the written word. The Discourses is a transcription of Epictetus' various lectures, recorded by his student, Arrian. Once, my lectures on political economy were transcribed for an entire semester for a hearing-impaired student, and I recall reading my spoken words with a sense of awe: how was it that I could speak such things but could not readily put these same ideas on paper? It is a powerful way to record ideas. The parallels between Epictetus' Stoicism and Christianity, especially the New Testament, are remarkable. Many of the key gospel sayings are apparent in Epictetus; work. This is not a new discovery - many have demonstrated the links between Stoicism and the Abrahamic religions, with Thomas Aquinas apparently quoting Epictetus in City of God - but some links remain confusing. For instance, Epictetus constantly refers to "god" (as opposed to "God"), but he is not always referring to Zeus (except were the name Zeus is used explicitly). The absence of the other Greek and Roman gods gives me the impression (managing one's "impressions" is a large part of Stoic philosophy) that Epictetus was a monotheist. I have discovered links between the Stoics and Ralph Waldo Emerson, but there is a difference that is worthy of further investigation, which requires a study of Kant. Epictetus' "god" is "immanent", meaning: "being within the limits of possible experience and knowledge". This contrasts with Emerson's "transcendent" God, where "transcendence" is defined in the Kantian sense as "being beyond the limits of of all possible experience and knowledge". I find the distinction between the Transcendentalists and the Stoics to be somewhat difficult to comprehend. For Emerson, God was in each of us individually, but what was in us was also part of a greater God that we all shared. If the Stoics' immanent god is wholly within our experience, as in, one's "acting in accordance with nature", or, to put it another way, one's "acting in accordance with god" - or otherwise suffering the consequences which include unhappiness, to the point where suicide, not through personal trauma, but for one's inability to act in accordance with nature, is a legitimate Stoic "opt out" action - but at the same time, being human necessarily means sharing fellowship in accordance with nature, then is this not Transcendentalist? Clearly, a thorough reading of Kant is required to comprehend this distinction. Yet Epictetus provides, for me, the most thorough understanding of Stoic philosophy. It is probably necessary to have a firm grasp on the ideas of Heraclitus, the works of Homer, and at least a working knowledge of Epicurus and the Cynics, but otherwise, The Discourses comes close to a practical religious handbook. I mean this in the sense that The Handbook (Enchiridion) is like an overview of Stoic thought, whereas The Discourses fills in the spiritual dimensions of the philosophy. I have often cringed when reading Atheistic and science-reifying comments about religion, but Epictetus does no such thing. It is apparent that faith and reason are not incompatible, and Nietzsche was right in that "God is dead and we killed Him". I have often met academic colleagues who will state that racism has no place in Academe, in that it has no basis in reason; yet applying the same argument to religion is a bridge too far. Epictetus makes it clear that faith and reason go hand in hand, in that first principles of Stoic philosophy require an understanding that acting in accordance with god (or God, does it matter?) requires faith in the existence of a god, which without would mean that philosophy is built on shifting sands, in that if God does not exist then there is no meaning to life. To be sure, to cling dogmatically to any one interpretation of the first-principle god would be to challenge the philosophy built upon it, but if one were seeking to apply faith and reason in one sitting, then The Discourses is the most comprehensible philosophy to do just that. And this, to me, makes The Discourses one of the most useful, insightful, and edifying books I have ever read.

View all my reviews

Donate

Donate

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View

The Political Flâneur: A Different Point of View